There exists a long standing tradition between nursing and statistics which has all but been forgotten. During my training to be a nurse, Florence Nightingale was barely mentioned. It was only when I started studying statistics, reading a book on the ‘great statisticians’, that I discovered her deep connection to the world of statistics. I’ve long since found it odd that the nursing profession eschews this aspect of our tradition, and that she seems more celebrated in statistics than she is in nursing. I took a trip to the Florence Nightingale Museum to see where this tradition started.

The Calling

Born in 1820 to a wealthy family, Florence and her sister, Parthenope, were unusual for women of the time in receiving a diverse education from their father. This included mathematics, which seems to have appealed to her penchant for collecting and sorting shells and coins. However, she was still a woman in her times and was expected to marry. Much to her family’s chagrin, Florence instead sought to flee the ‘tyranny of the drawing room‘.

Florence felt a calling to service and after ministering to her family and servants during a flu pandemic she felt God was calling her to nursing. This was quite the shock to her family, for nursing was working class work with a reputation to drunkeness: not for women of her station. For a long time she was forbidden to pursue her passion and suffered a period of ill-health while she studied nursing in secret.

Finally, she was allowed to train as a nurse in Germany and then, using her affluent connections, became a superintendent at a Harley Street Institution.

The Journey

Just as Florence was contemplating training her own nurses in London, the Crimean War broke out. The war was one of the first to be documented in the media, and among the reports were the terrible conditions faced by the soldiers accompanied by calls to modernise medical practice. Upon this wave of public and political will Florence was tasked by the secretary of health to lead a team of 38 nurses to Scutari, an army base hospital in Constantinople, housing the sick and wounded from the war.

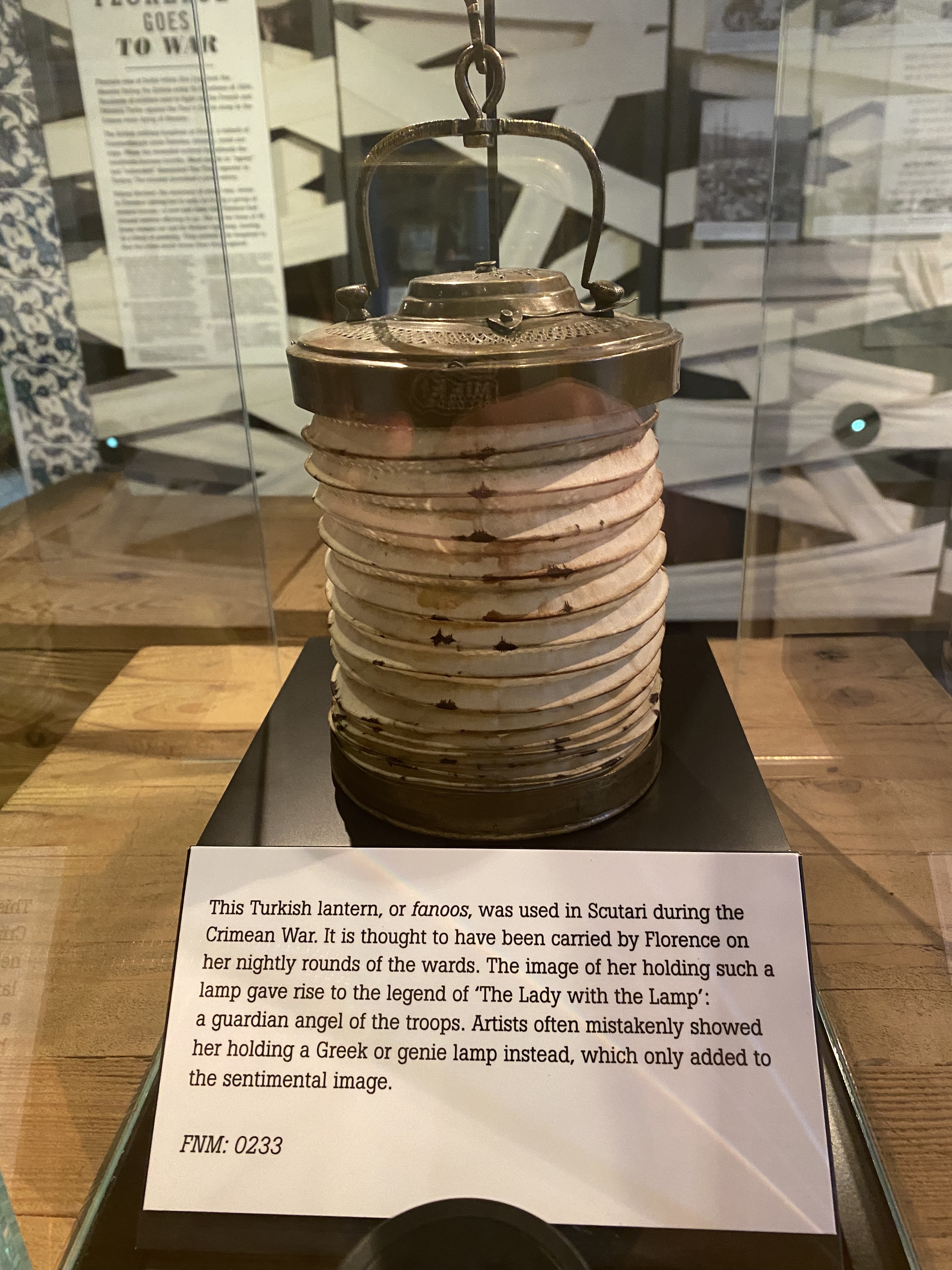

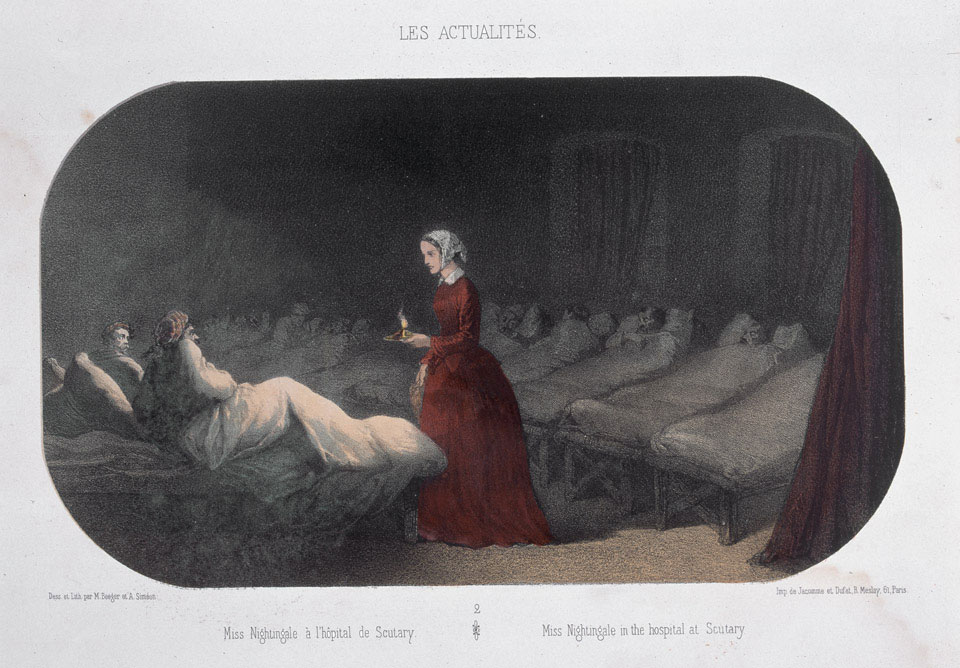

Conditions were horrific, Florence describing it as the ‘Kingdom of Hell’. She set about a program of cleanliness – this decades before Pasteur and Koch finally convinced physicians of germ theory – securing supplies with financial help from the media and enlisting soldiers’ wives to help with laundry. With high standards of care and professionalism she was able to win over a deeply sceptical patriarchy of medics. She also attended to the soldiers’ psychological needs by assisting with writing letters home, establishing non-alcoholic drinking venues and providing educational and recreational outlets (surprising officers who thought the soldiers illiterate). The genesis of modern nursing was truly holistic. It was in this time, when she would inspect the wards at night, supporting those in need (I’m certainly grateful to a few duty managers for their support during some lonely night hours). Thus, she became the Lady of the Lamp.

Florence then toured field hospitals in Crimea itself, and here she contracted a disease, thought to be Brucellosis, that would blight her for decades to come. She remained in Scutari until the hospitals were ready to close in 1856, returning to England the reluctant hero.

Left: a Turkish Lantern on display at the museum that used used in Scutari. Right: Coloured lithograph, Max and Simeon A Beeger, 1856 (c). No 2 in the series ‘Les Actualites’. Artists often mistakingly depicted Florence with a Greek or genie lamp.

Data Scientist

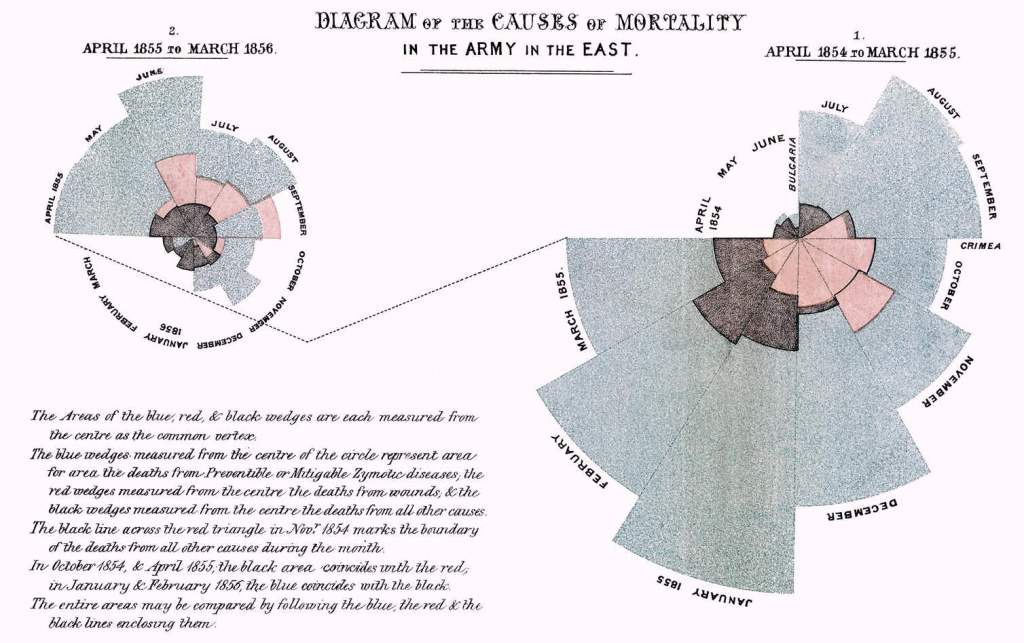

Historians generally agree that Florence’s contributions during the war are exaggerated but this is true of any individual whose exploits become mythological. However, her later contributions, while perhaps less media friendly, are widely considered to be society changing. Her great contribution resided in her ability to create a narrative based on data, starting with her data visualisation techniques.

This had started in Scutari, where she found the hospital records in as a lamentable condition as the wards. Even deaths were not accurately recorded, with three seperate registries giving different accounts. Once data cleaning was implemented (the first role of any statistician and data scientist, though few would pursue it right to the front lines), Florence was able to show that, during the first seven months of the campaign there was a 60% mortality rate from disease alone: exceeding that even of the Great Plague in London. She also showed that mortality by disease was seven times greater than by enemy fire.

Later at home during peace, Florence showed that soldier’s mortality rate was higher for age matched men in England. Strong words accompany her bar chart.

“it is as criminal to have a mortality of 17, 19, and 20 per

thousand in the Line, Artillery and Guards, when that in civil

life is only 11 per 1,000, as it would be to take 1,100 men out

upon Salisbury Plain and shoot them.”

Much of her findings emanate from a report, written in six months while she was still convalescing titled Notes on Matters Affecting the Health, Efficiency, and Hospital Administration of the British Army. The data visualisations were innovations of the day, at the very cutting edge of scientific reporting. This is no trivial matter; the art of communication is as important as any other step in the data sciences, for if we fail to persuade anyone of their value then all else is wasted.

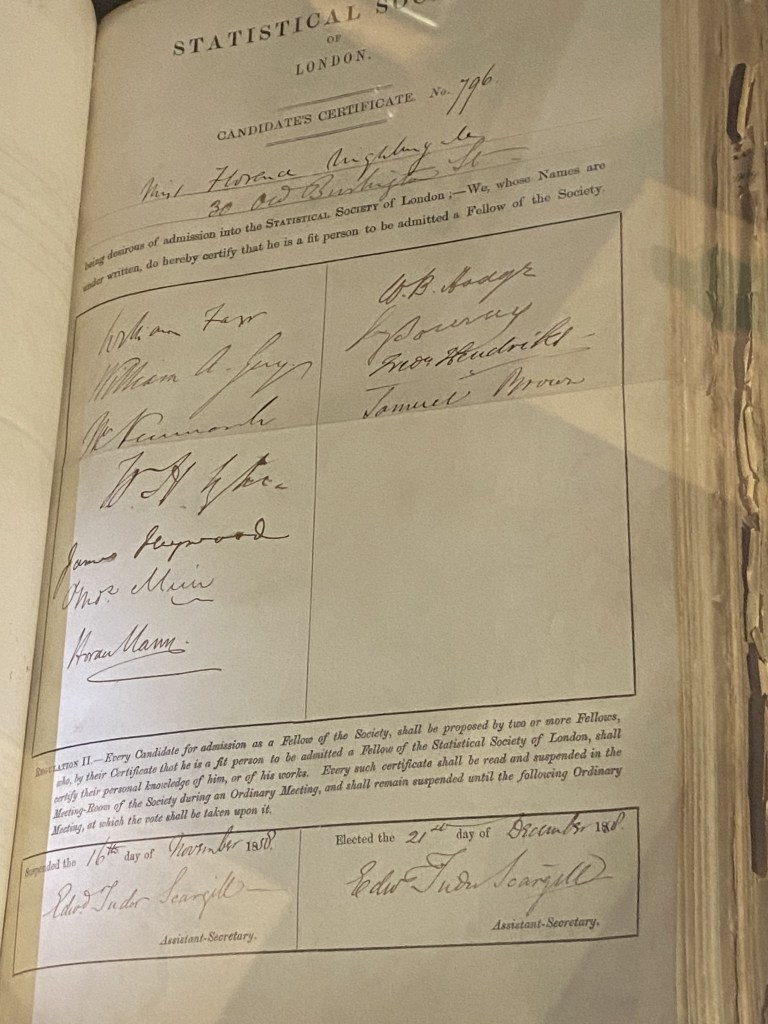

She also made significant inroads to standardising the collection of hospital statistics, which barely existed at the time. This made it it possible to actually examine mortality and morbidity across various sub-divisions of society. This was ‘big data’ of the Victorian age. Her contributions are too numerous to explain here – for more details on Florence’s statistical works, I strongly recommend this article by Edwin W. Kopf. In short, her use of data is not over-stated. In 1858 she was elected to fellowship in the Royal Statistical Society (and in 1874 made an honorary member of the American Statistical Association).

She also contributed to hospital design in a collection of papers called s “Notes on Hospitals”. This surprised me, though perhaps it shouldn’t have, for I have worked on a Nightingale ward: though out of vogue now, I must admit I preferred its open plan which allows nurses to easily observe all patients on the ward.

Another little gem I discovered in the museum is that, amongst others, Nightingale corresponded with mathematically minded people such as Ada Lovelace. Little seems to be known about their interactions other than a mutual respect for each other’s work (at least I couldn’t find anything, leave a message if you know otherwise). What little branch of computational medicine could have flourished had the difference engine been completed?

Legacy

Some think it odd when I tell them I used to be a nurse before moving into the computational sciences, but really I’m just following a tradition started by the founder of modern nursing. What I find strange is that more nurses haven’t followed Florence’s light. I believe that knowing the heritage and legacy of your profession is important for many reasons. As someone in nursing, and with a latent interest in mathematics, Florence would have been an inspirational figure to me. But none of her legacy did I discover until I left nursing.

Why is Nightingale largely forgotten in the nursing curriculum? I have no idea. Perhaps it was only where and when I trained and she is studied elsewhere. If you are a nurse, particularly an educator, I would love to hear your thoughts and experiences. But I know I am not the only one who was ignorant of our heritage; I personally know of others who have left nursing to pursue data driven and computational paths, not knowing it was always a part of our heritage, through Nightingale’s legacy.

The main end of statistics should not be to inform the government as to how many men have died, but to enable immediate steps to be taken to prevent the extension of disease and mortality

from Notes on Matters Affecting the Health, Efficiency, and Hospital Administration of the British Army, Florence Nightingale, 1858. This was a 830 pages of analysis and proposed reforms.

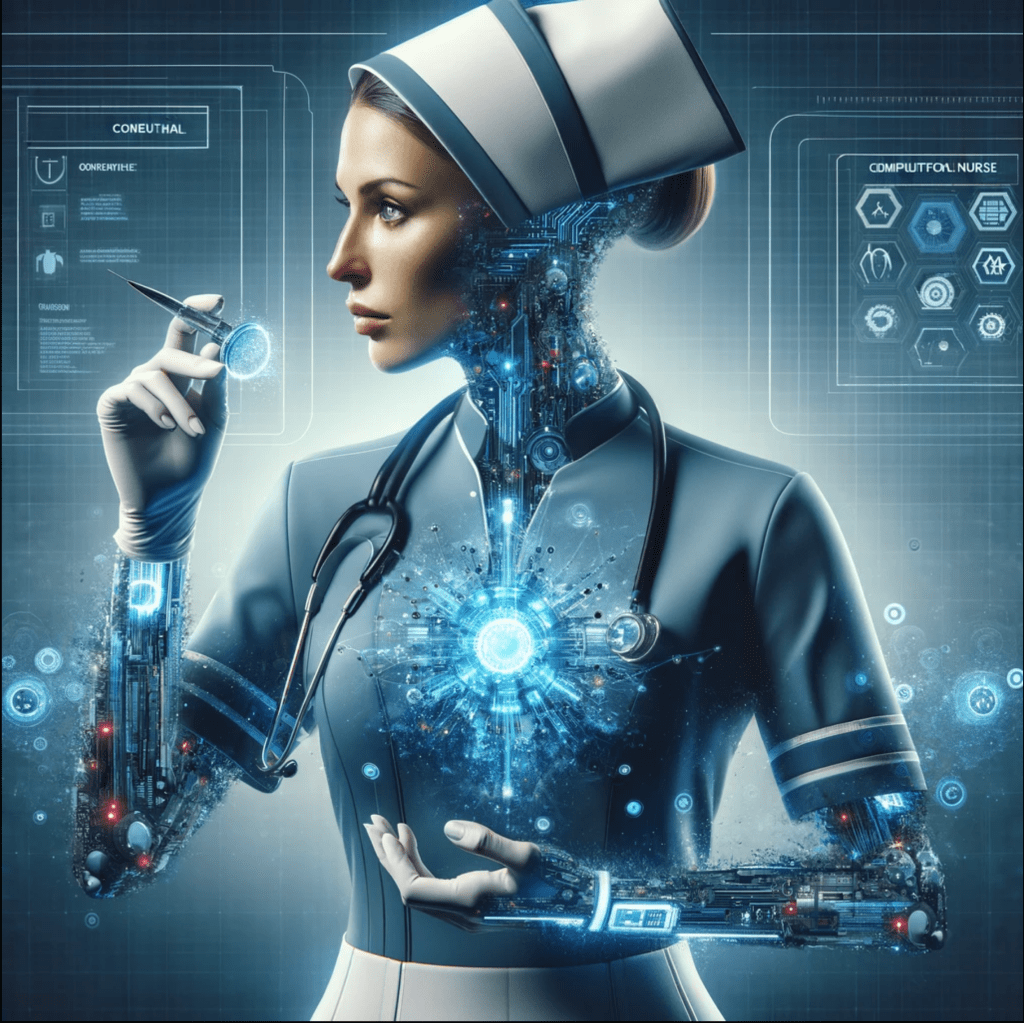

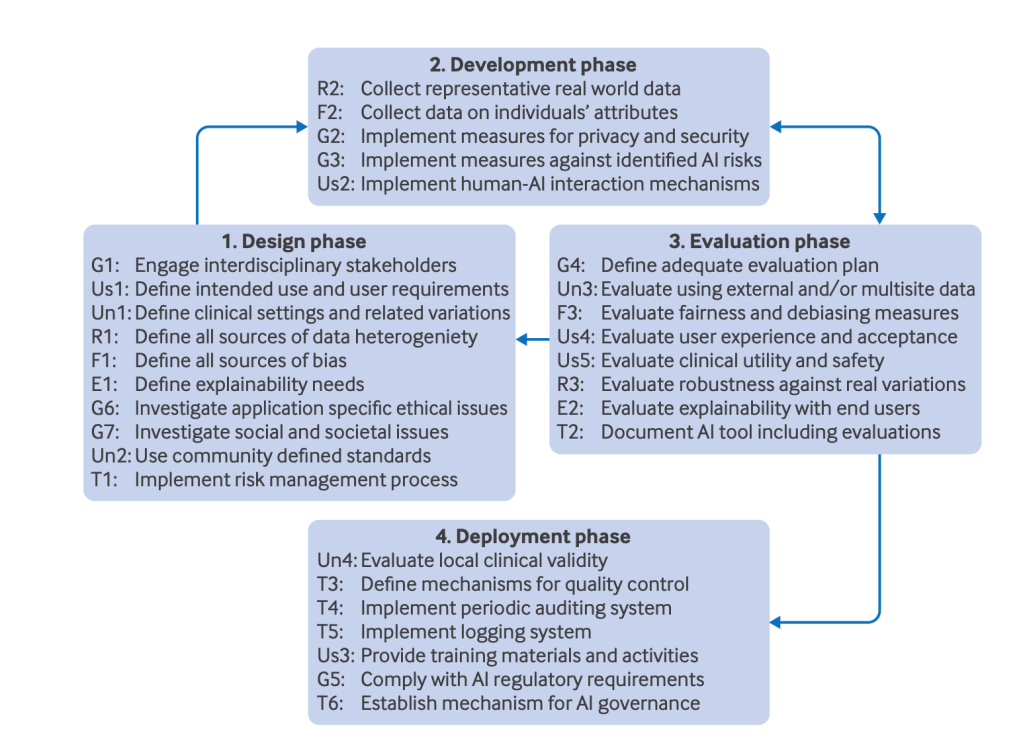

Health statistics are more important now than ever before. We have unprecedented, and increasing, amounts of data to contend with. We have tech companies and governments vying for our medical data. We have streams of data from wearable devices from healthy populations, pushing the boundaries of health and disease. And with the increasing use of ‘black-box’ AI – machine learning in which the predictions become ever more accurate, but the interpretation becomes ever more obscure – we have the possibility of non-human decision making. I’ll be exploring such topics in future posts.

Leave a comment