As this platform is given to the exploration computational medicine, a reasonable first question is just what is it? One way to approach this is to understood it in the wider context of computational modelling in the sciences that has been gaining traction as computers become ever more ubiquitous and powerful. But this is just delaying the diagnosis as it begs the question of what is computational modelling. Once we answer this question, we can then see how it particularly applies to medicine.

Computational vs Mathematical Modelling

A mathematician once told me he thought that mathematics was woefully inadequate to model biological phenomenon. This, despite being a lecturer in bioinformatics at UCL. Biology is just too messy. This was aptly demonstrated by a system of hundreds of differential equations used to, very crudely, model intracellular transport. There were too many assumptions, too many estimations and the system too complex and sensitive to survive such coarse graining. This is not to say that differential equations don’t have their place in modelling biological systems, but it’s clear that their contribution to biomedicine won’t be nearly close to that seen in physics.

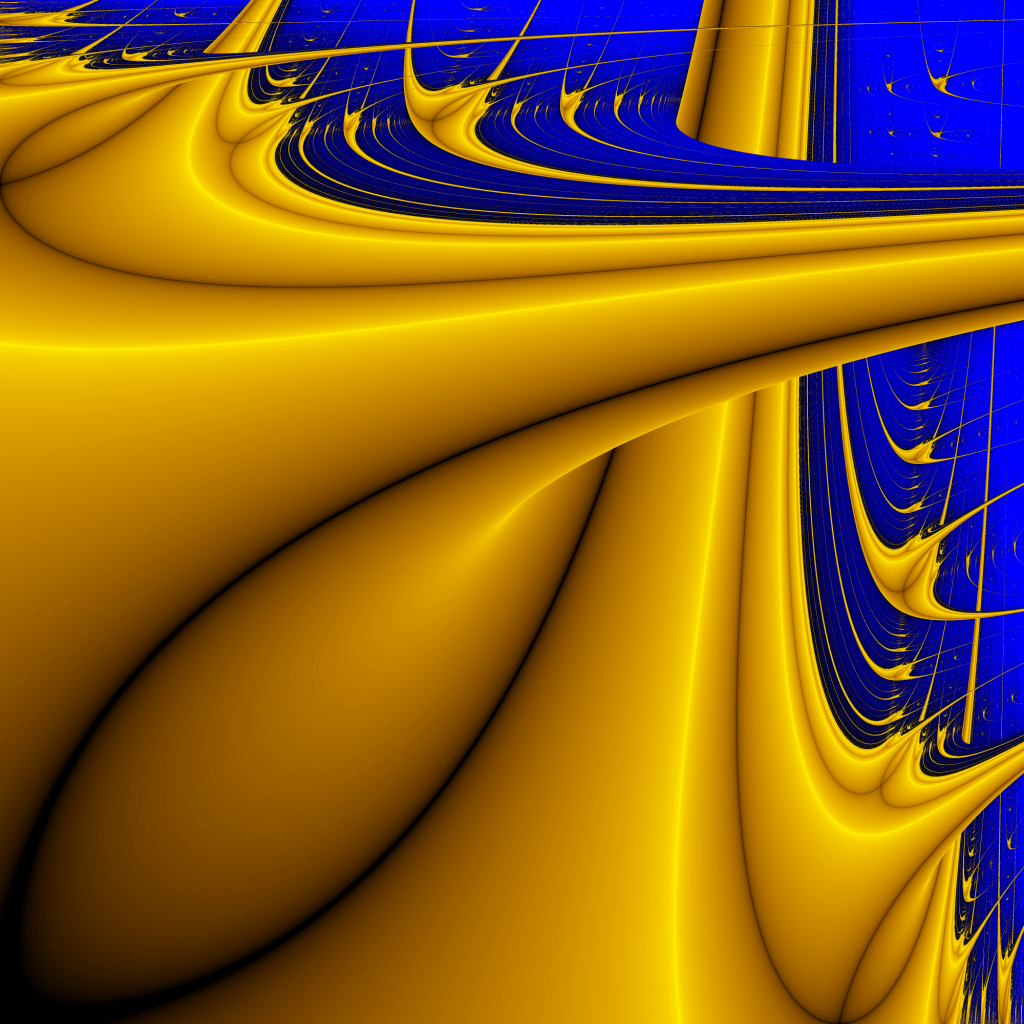

One might ask, as did Eugene Wigner in 1960, just why mathematics is so unreasonably good at modelling any physical phenomenon at all. We are, perhaps, a little closer to answering why mathematics works for modelling relatively simple systems but not much more complex systems typically found in biology. Many a scientist has, in one way or another, called attention to the surprising fact that despite the overwhelming complexity of the fabric of existence, there are enough regularities woven into it that we can untangle laws of nature. Schrodinger (in What is Life?) commented that the fact there are any regularities at all amongst the baffling complexities may forever be beyond human understanding. However, the idea of reducible and irreducible complexity may provide a framework to aid our understanding. This posits that there may be certain phenomena which can be predicted in fewer steps than the phenomena itself takes to unfold, while in an irreducible phenomena there are no such shortcuts to prediction. My favourite illustration of this are the Lyapunov fractals derived from logistic maps (used to model population growth – this video provides an excellent explanation). The Lyapunov exponent, λ, determines whether a system is stable and predictable (λ < 0) or whether it becomes unstable and unpredictable (λ > 0).

In mathematical modelling we may consider that the model is first constructed and then it stands or falls upon the winds of nature, preferably via experimentation where it can be protected from the buffeting turbulence of potentially confounding factors. The actual human process is likely more complicated than that, involving keen observation and deep rumination on the part of the practitioner, but since I have not had such deep insights, I can only speculate and admire those who have. In computational modelling the data comes first and the model is shaped around it. Of course this comes with its own risks, overfitting not least amongst them, but it provides another means by which to make predictions. At first glance computational modelling may seem indistinguishable from mathematical modelling, both replete with equations and drawing quantitative inferences. However, it seems to me to be more than just another tool in the scientist’s kit, but rather a fundamentally different way of approaching modelling. Instead of starting with a model and acquiring data to disprove it, we first acquire the data and shape our model around it.

The question is then whether computational modelling can do any better for predicting phenomena existing in the chaotic regions of medical research.

Computational Modelling

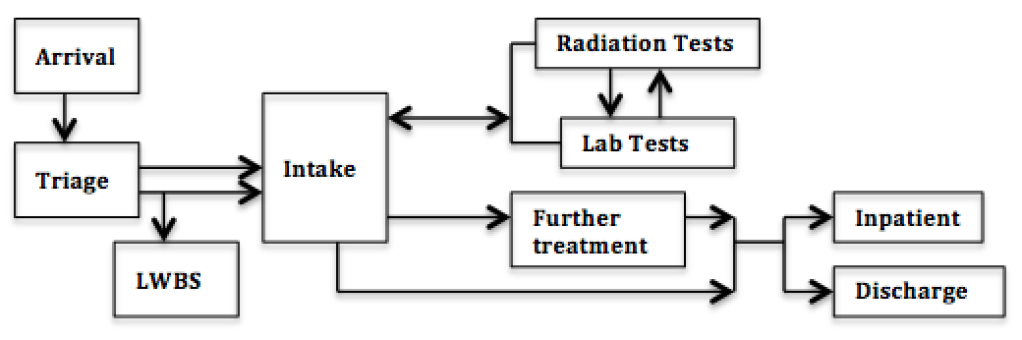

Computational modelling is more than just using computers to model something. Cellular automata are excellent examples of computations that can be performed by ‘hand’, the only limitation being tedium and the finiteness of our lives. I belatedly realised the power of computational modelling when trying to model the flow of patients through an accident and emergency (A&E) department. The idea was to have a model of sufficient fidelity to the real system so that we could observe bottlenecks in the department, and ask seemingly simple questions such as what would happen to the flow of patients if we adjusted nurses’ break times. I took the classic statistical approach of using a Poisson process to model the arrival of patients to the department. This was extended to model arrivals to certain areas of the department (triage, radiology, treatment areas and such). But the model was never complex enough to be useful. While I was fiddling with parameters and contemplating ever more exotic mathematical techniques, I had the nagging suspicion that this would all be much more amenable to a good computer simulation. But I was determined to find a mathematical solution and never did pursue the computational route. I have long since abandoned that project, but I (eventually) learnt the lesson: mathematical modelling alone won’t solve every problem. (Anyone interested in pursuing similar projects let me know).

Computational modelling is in some sense theory agnostic; such a model is ‘good’ only in so far as it is ‘accurate’ (precisely what we mean by accurate is a question for another day. Suffice it to say, in the context of medicine, useful). However, agreement between prediction and observation alone is not generally sufficient for us to say a theory is correct. Ptolemy’s theory of epicycles is accurate with observation, indeed was more accurate than Copernicus’ early heliocentric model (with its circular rather than elliptical orbits), but has long since been discarded.

DeepMind’s AlphaFold provides a more recent case study with its successes in ‘solving’ protein folding. From a strictly medical perspective, AlphaFold would be stunningly successful if it helps, for instance, find therapeutic targets in such a way as to expedite the drug discovery phase of clinical research (despite the hype, it remains to be seen just how useful it will be). However, as explained by Janet Thornton (director of the European Bioinformatics Institute) AlphaFold does not ‘solve’ the protein folding problem because it does not provide, or even develop, a framework to understand why it works. It is a theory free approach, concerned only with its predictive power.

For many medical applications this will be sufficient. It has been argued that the current medical scientific paradigm (Evidence Based Medicine), is predictive rather than explanatory. Take, for instance, the humble paracetamol (acetaminophen), in use for over a hundred years, yet we have only a partial understanding of how it works. We do, however, have a thorough understanding of its efficacy and safety profile; we may not know precisely how it works, but we know that it works, and under what conditions it becomes dangerous. This is true of a raft of medications, from antidepressants to anaesthetics. A surgical colleague of mine even thought it true of gastric bypass surgery, even though it seems to have an obvious mechanism (would love to hear comments from any bariatric surgeons out there about this).

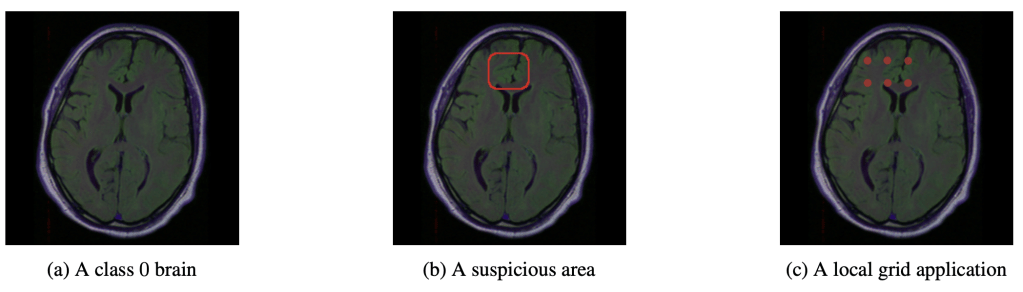

If medicine is more concerned with predictive power, then computational medicine provides a potent tool. The success of AlphaFold suggests that computational medicine can make more accurate predictions than traditional modelling in the more complex realm of biomedicine. The race is now on to apply similar techniques to the various -omics datasets, from metabolomics to transcriptomics as well as interpreting various imaging modalities from x-rays to PET scans.

Big names in the AI community such as Ilya Sutskever and Gary Marcus have described deep learning, the current epitome of computational modelling, as the alchemy of our age. This is meant as a put-down, but this ignores the historical role of alchemy in the development of modern science (indeed, Newton was an alchemist). Despite its (often deserved) reputation, alchemy was crucial to the development of our thinking, eventually leading to more robust ideas that coalesced into modern chemistry. If nothing else, it enshrines the idea that there is an underlying theory to observed phenomenon. What then is the path to bringing computational modelling to a more theory-based, human-centric understanding of the world? I don’t know, but I look forward to exploring that path. I think one interesting fork is the developing field of explainable AI, which asks what features of the world (or more strictly an AI’s world, for their inputs are still very limited) is an AI system using in order to make its predictions. This, under the auspices of Hana Chockler, is the topic of my post-doc research.

Whether computational medicine lives up hyperbolic expectations, falls under the tide of the current hype cycle (no doubt only to resurface under a different name) or finds some middle ground will be an interesting journey to follow. Let’s remember, as the statistician George Box said, all models are wrong, but some are useful.

Leave a comment