In 2016 Geoffrey Hinton made a now infamous prediction about AI being good enough to make radiologists redundant.

If you work as a radiologist, you are like Wile E. Coyote in the cartoon. You’re already over the edge of the cliff, but you haven’t yet looked down. There’s no ground underneath. People should stop training radiologists now. It’s just completely obvious that in five years deep learning is going to do better than radiologists.

There’s a smugness to it that is unbecoming, like radiologists are oblivious that the very ground beneath them has gone. It’s in poor taste, but if everything I ever said was held up to such scrutiny I’m sure I’d also be found lacking. The more pernicious part is that he recommends that radiologists should stop being trained. This is actually dangerous. Hinton is now a Nobel prize winner – a politician who doesn’t know any better might actually listen to him. Worse yet, an aspiring radiologist might decide to go into another speciality. This at a time when there is a growing global shortage of radiologists (and histopathologists). Yet it’s all completely obvious, apparently. No, I think Hinton deserves all the stick he gets for this one. But the more interesting questions are why medical AI tasks are so much harder than general ones and why I think we’re still very (very) far from medical AI that is ‘better’ than healthcare professionals.

Quantity – but quality?

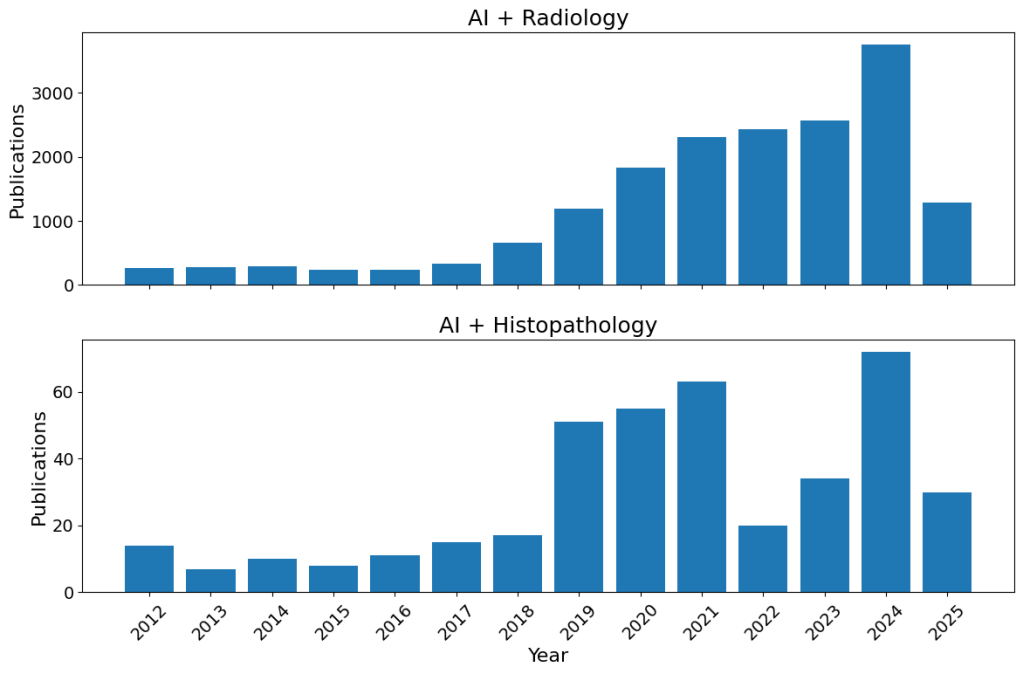

There is certainly a proliferation of medical studies being published related to AI. It might be tempting to think this is all building towards great advances, but let’s look a little more closely.

The proliferation of “AI” studies in radiology and histopathology. I wasn’t expecting histopathology to be quite so far behind, and I have no idea what that 2022 dip is about (maybe Covid related as focus went elsewhere – I personally know of histopathologists being sent to the wards, but not any radiologists). This was a back of the envelope code (if that’s a thing), so maybe I just made a mistake.

There is a study of Covid chest radiographs using machine learning (before AI became a buzzword). It first culled about 250 studies of insufficient quality on first inspection. Of the 62 studies that received a thorough investigation, precisely zero were found to be clinically relevant. Some of these are articles which people outside the domain could cite as evidence that ‘AI is already as good as clinicians’. Which is not to say all those studies were rubbish and a waste of time; many focused on some tiny technical aspect, progressing science a tiny bit at a time (how science progresses when not in the headlines). But this is where medical AI really is: slow increments, not a revolution.

Even Nobel prize worthy Alpha Fold has yet to make any actual clinical impact, expediting no drugs to market yet (three in pre-clinical trials as far as I can count while writing this). Again, this is not to say Alpha Fold is useless (it’s probably the current best application of AI in the biomedical space), just that it’s fruits were always only ever going to be small, and they take time to ripen. Incremental, not revolutionary.

But this all begs the question of why “AI” is harder in the medical domain.

Medical images aren’t like cat and dogs

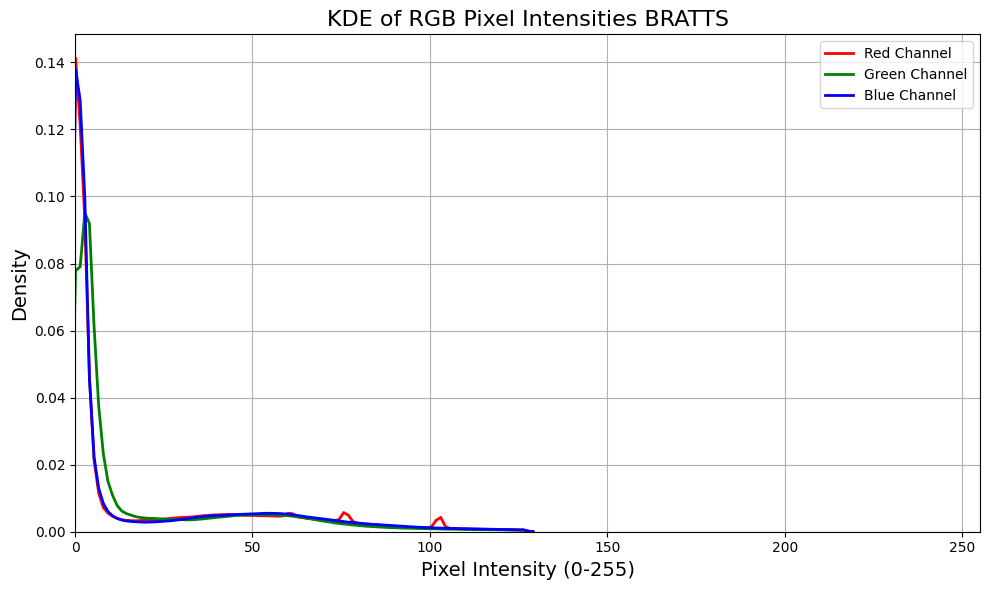

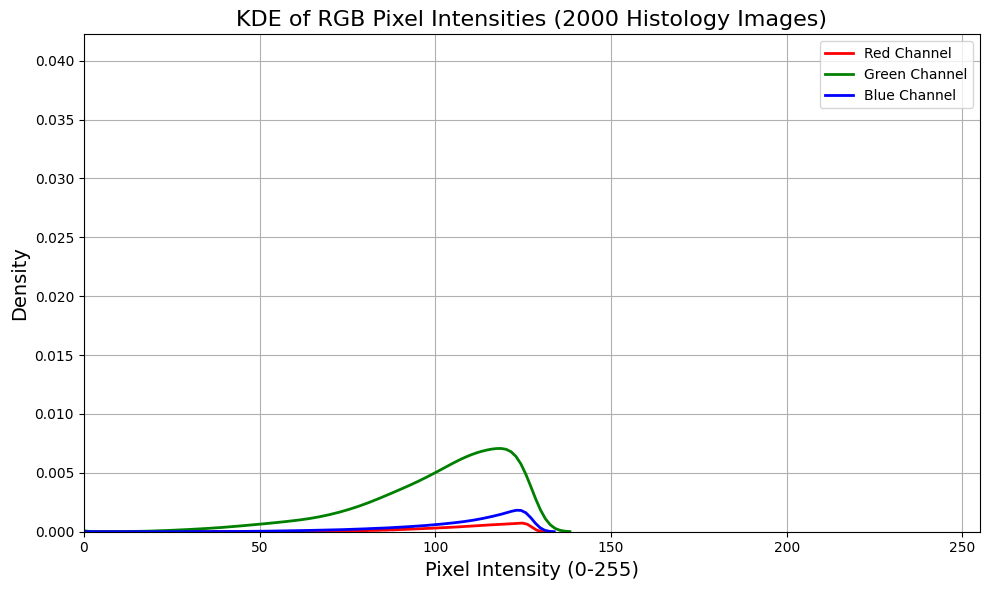

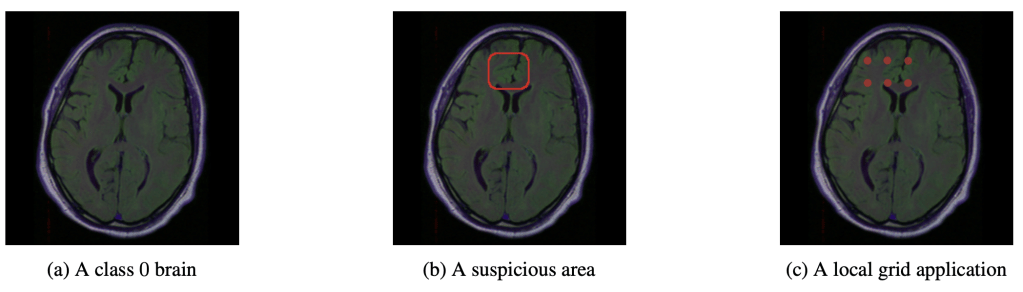

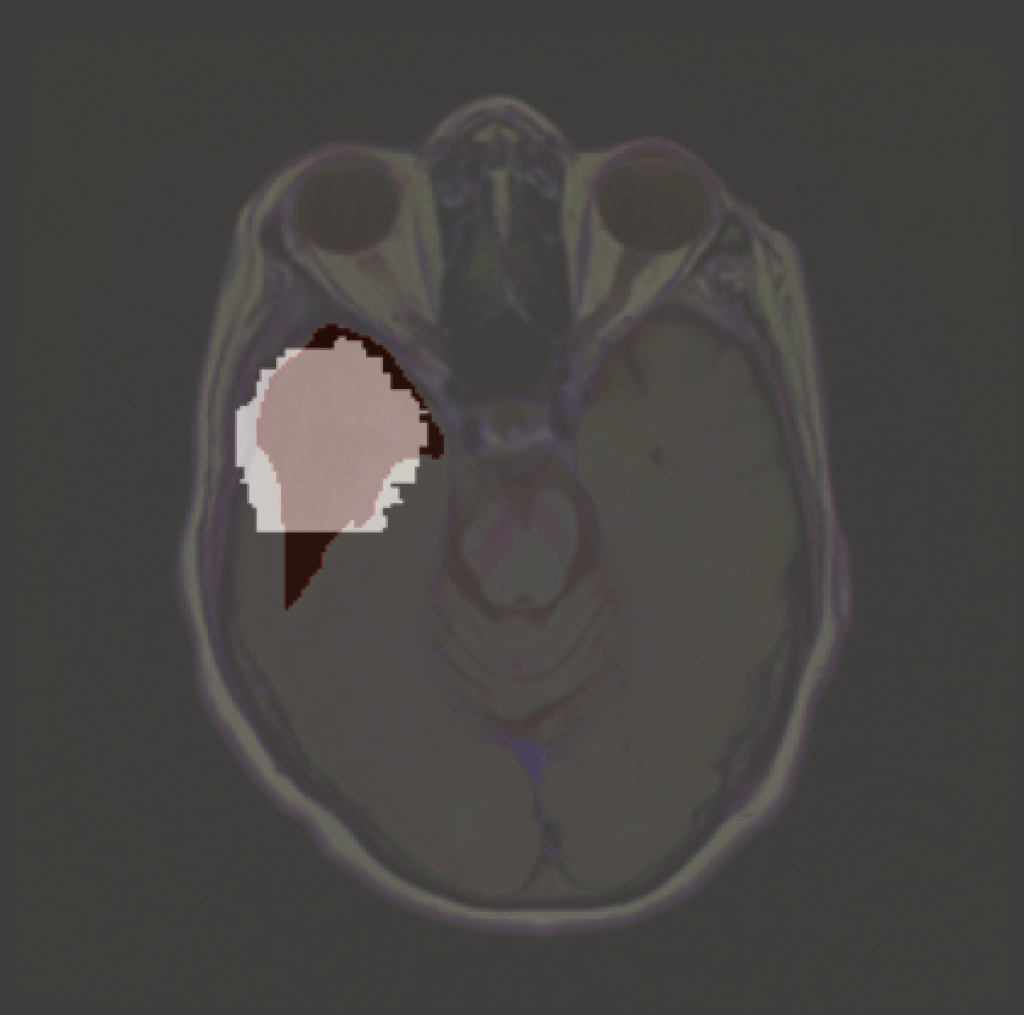

Relative to every day images of cats, dogs, boats and meat loaf, medical images are far more homogenous in terms of the distribution of RGB pixels (or equivalent). On top of this, the categories of interest (e.g. disease categories) are much closer to each other. It’s actually possible to train pigeons to accurately distinguish between binary disease/healthy medical images (yes, someone did that experiment) – but far harder to distinguish the shades of grey in between. These combined mean the input space is just a far more crowded space, and so learning a decision boundary is harder than for regular images.

For a quick illustration I took a random subset of 1500 images from the STL-10 dataset (every day images), about 1500 MRI slices from BRATTS (not RGB but T1, T2 and T2-FLAIR) and a few thousand tiles from breast whole slide images. Using kernel density estimation for convenient visualisation we see that medical images, before normalisation (although there’s almost certainly some pre-processing done to these images, particularly BRATTs, before making them publicly available), are far less distributed over the potential pixel space. Of course there are lots of tricks to mitigate this, but it illustrates that medical images are typically more densely packed in input space, making separation harder than more dispersed general images.

In addition to this, medical datasets are often hierarchical in nature. A single patient might have multiple biopsies taken from a similar region, from which each region might result in more than one sample, and from each one of these multiple data points might be taken (as happens with Raman spectroscopy, for instance). Assuming a flat structure is one of the quickest ways to get impressive sounding results which make it sound like AI is out-performing humans, but can’t generalise to the clinic down the corridor. The lack of generalisation is such a problem it has a name in the medical literature: the generalisation gap, which sits alongside the reproducibility crisis where impressive AI results can’t be replicated elsewhere (though this is far from unique to AI).

Add to this a general lack of medical data, a lack of accurate labels with what data we do have, which are often highly imbalanced and it’s easy to see why machine learning in the medical context is a much harder task.

Higher Standards

Medical applications also have a much higher bar than many other applications; rightly so. Ignoring the many shades between, there are two ways a prediction can fail – either a disease is present and an AI predicts its absence, or the disease is absent but the AI predicts disease. All else being equal, there is a trade-off between these, but it is not as simple as weighing towards the former. It might seem sensible to err on the side of caution and prefer an AI to over predict disease to ensure it doesn’t miss the real disease. But this wouldn’t work in a screening scenario, where false positives inflict pain (biopsies hurt) and cost money and significant psychological suffering (try waiting for biopsy results after a ‘positive’ mammogram).

Generative AI is being explored for many medical applications (I’m starting to use it in my own research to generate ‘healthy’ counterfactual images of occluded portions of medical images). In a histopathology image, say, what is the equivalent of the smudge of fingers that is current generative AI? We don’t know, making it all the more necessary for it under severe scrutiny.

No one is saying that AI should never be wrong, far from. Demonstrating non-inferiority to experts is sufficient if it provides other benefits (e.g. cost, time, accessibility). But it’s failure modes must be understood at least at an empirical level (i.e. we observe an AI to fail in scenarios x,y,z… even if we don’t know why). Empiricism takes time, especially in a medical context and there are just no (safe) shortcuts. But more on that later.

Dodgy datasets and bad benchmarks

I’ve talked about Frankenstein datasets elsewhere (where a dataset curator will inadvertently add many replicates of the same sample in an attempt to boost the sample size), but the problems with datasets go much deeper. There is generally a lack of publicly available benchmark datasets of sufficient quality to assess models – it is difficult to get both quality and quantity. Many models are trained on private/siloed datasets and then tested against public benchmark datasets. While great for transparency, and providing a common dataset for assessment, such datasets are often very small and homogenous compared to the target population to which a model should generalise.

Benchmarks just aren’t real life and there are many reasons while great results don’t generalise – good performance is a promising start, not a reason to declare AI is already superior to clinicians.

What you looking at?

There’s a gap between what AI developers and clinicians expect AI to do. The former hope that AI is able to identity subtle and novel features that are hitherto unknown to the medical establishment. While theoretically possible, all the above issues would first need to be addressed. But even then, clinicians would prefer AI to make predictions based on current medical knowledge. Some of this is a trust issue, and given how biased AI is and how it fails to generalise this is just good sense. But there’s also a legal issue here: why would a clinician trust an AI model to make a diagnosis when it’s the clinician who will take legal responsibility for getting it wrong. This will be one of the acid tests for medical AI – when a tech company is happy to take legal responsibility. But if that AI is making recommendations based on the existing evidence base, then there is a path forward.

Many are attached to the idea of AI surpassing expert humans. But within the current regime, this can’t happen. Ultimately AI still relies on humans to label the data (notwithstanding various techniques to provide unsupervised components for unlabelled data), and that is a ceiling. A shift to outcome based AI (i.e. mortality and morbidity as the learning signal) would be a significant step forward. This would allow a model to pick whatever features best capture whatever is driving a process to deleterious health, without relying on often zuzzy intermediate human labels. However, this requires us solving many practical problems: how to deal with longitudinal data; how to model under the uncertainty of missing values and irregular intervals; how to find which novel biomarkers the AI is actually identifying and then to verify those biomarkers as predictors of disease. This is decades of work to become truly robust. Yes there are plenty of historical tissues and images, but they are stored in silos with limited access. Even if you get access to that data (and especially the metadata) it is messily labelled, if its present at all. Historical samples and data weren’t collected with AI in mind. All of these problems can be overcome, some with technical innovation, some with streamlining logistical and regulatory processes, but it all takes many years if not decades.

And we haven’t even begun to tackle the issue of how much knowledge falls through the cracks and simply isn’t represented in ANY data captured on health records, paper or electronic. The subtle corrections the radiographer is making to account for the particularities of that CT scanner; the time a patient tells a nurse their darkest fears which just can’t be articulated in any medical jargon; the doctor who just loves prescribing PPIs with every other drug (you know who you are). Most medical knowledge is of this intangible kind (the vast majority I’d wager)- humans are so adept at navigating these complexities we don’t even acknowledge it as a skill. When AI can perform the seemingly hard tasks, like reading an MRI scan, we just assume it can do the ‘easy’ stuff. This is Moravec’s paradox; it’s not nearly enough known about.

Better Together

What does ‘better’ actually mean? For some tasks this might seem obvious – can an AI predict better than a human, and ultimately can it construct and execute (or get a human to execute) a plan which extends life and limb. But health is one of those concepts, like life and time, which is surprisingly resistant to a simple definition (don’t believe me? You’re probably still too young to observe how your own definitions of good health shift with age).

I expect AI to fail in many cases, just as the very best of human experts. But if we build AI which fails in a different way to humans then we have built extra robustness into the system. If, however, clinicians become complacent and let a few early successes drop their guard then we’ll end up with the clinical equivalent of vibe coding: I can imagine patients suffering while bureaucrats insist performance metrics are improving. AI certainly provides another avenue for Goodhart’s law to manifest.

An excellent example of this teaming is in surgical robotics. While robotics has improved surgery, it is all operated (or tele-operated) by humans. I’ve heard of one autonomous robotic system able to place sutures in porcine intestine, though this still required human supervision. This shouldn’t be a surprise – if we don’t yet have fully automated cars (and from what I understand it’s not on the horizon with current tech), how much further are we from fully automated surgical robotics? (Genuinely not sure which is the more complex task – humans would certainly think surgery, but beware Moravec’s paradox). However, we still get predictions like this (from Musk this time):

Robots will surpass good human surgeons within a few years and the best human surgeons within ~5 years.

No. All the cutting edge research, that might actually make it to an operating theatre (for the rich, at least for now), will be combining robotics and humans, using the strengths of each to cover for the weaknesses of the other. Good clinically deployed AI in more general settings will be the same.

Predictions

I was going to end by drawing attention to one of the best research programs on clinically deployed AI, but this blog is too long already. This breast cancer screening program might be construed as ‘AI surpassing humans’. All I’ll say is read the full thing and not the press releases.

Instead, I’ll end by noting that specialists no better than lay people at making predictions. I think Hinton falls squarely into this camp, blinkered by his expertise rather than aided by it. Ask anyone with a foot in both the AI and clinical domain, and predictions for AI supremacy gain decades.

Hinton at least stuck his head above the parapet and made a solid prediction, so it’s only fair I do the same after giving him some stick. It is completely obvious that AI will not outperform clinicians in any real world clinical setting within the next five years. Instead, we might start to see AI + human teams outperform human only teams in certain clinical areas, in a slowly increasing trend (until something like active inference matures).

Leave a comment