Large language models are seemingly everywhere, including the medical literature. They are either poor medical coders or a panacea for medical practice depending on, perhaps, whether you are regulating them or selling them. Their use has been explored in several clinical settings including generating and extracting information from medical reports, performing triage, even use as conversational agents for mental health support.

As part of the growing need for computational literacy amongst medical practitioners, here we explore what LLMs are, their putative clinical uses and their potential pitfalls.

What are LLMs?

An LLM is a type of generative AI which takes in a text (and increasingly images) input and returns a text output. They are finding all kinds of uses from content generation (anything from essays to financial reports), language translation, virtual assistants, creative writing and even data analysis. They are typically based on the transformer architecture, a type of deep learning model. These models deal in ‘tokens’, fragments of words or punctuation and it is these tokens which LLMs sequentially generate.

Their applicability to many professions, from finance to law, is being debated. They are either stochastic parrots, simply repeating what they have been trained upon – generating some ‘average’ output, or intelligent agents able to think and reason, one step away from AGI. In the context of clinical practice, they are are potentially useful tool, but just as anyone trying to hammer a nail with a screwdriver with a nail can tell you, you most know how, and when, to use any tool. While much has been promised on behalf of LLMs, it is the responsibility of any healthcare practitioner using them to understand any tool they use.

Why are LLMs relevant to medicine?

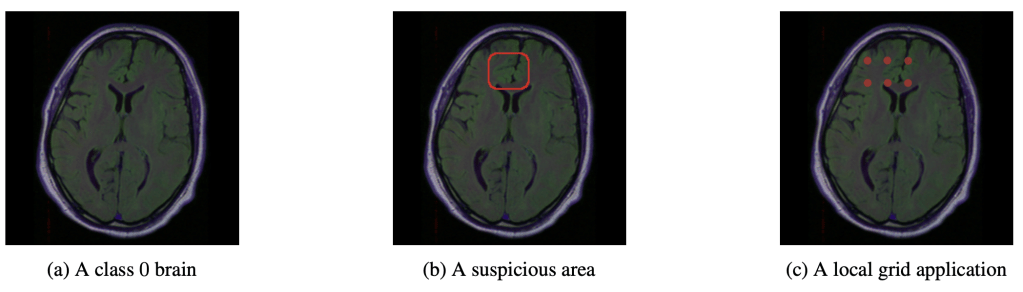

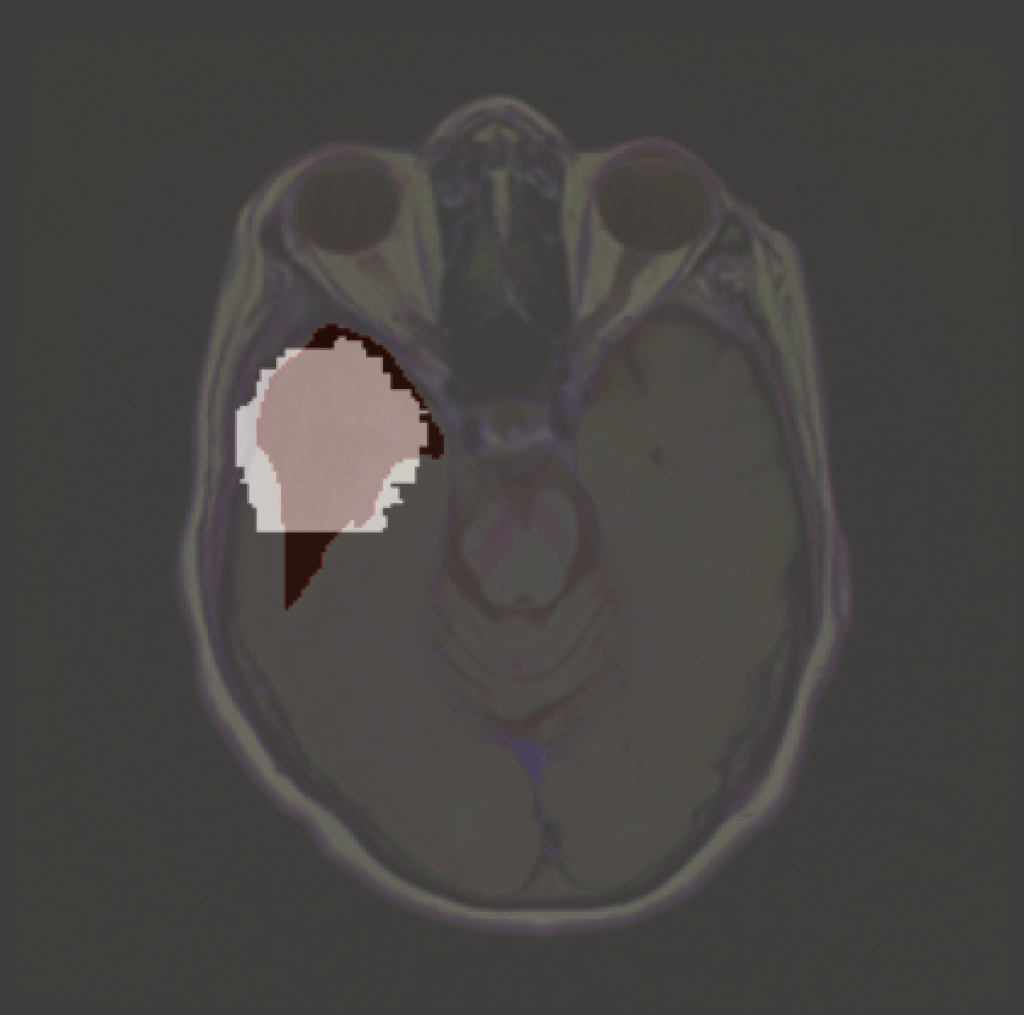

LLMs have yet to be established in any healthcare domain, and it is debatable they ever will in their current form, but many potential uses have been explored. This includes ‘extracting actionable information from radiology reports‘, triaging accident and emergency patients; they could see roles in translation, providing summaries, standardising documentation. One vision imagines all medical literature being produced by LLMs. As we’ll see later, it could even generate reports given a histopathology or radiology image. In the last week alone I have received two requests to peer review articles assessing LLMs in A&E (prompting me to write this blog).

The potential uses are legion and there is something of a wild west attitude as people seek to find the next killer app. But the stakes are much higher with medical applications: below are some of the things I look out for when assessing the applicability of medical LLMs.

Are LLMs deterministic?

This is not an issue I see discussed much, but I feel it important, certainly for medical researchers. Given the essential role of replicability in evidence based medicine, it is reasonable to ask whether the outputs of a LLM are deterministic: given the same input, will the same LLM give the same output. It would not do to have the LLM recommend one course of action to, say, triaging chest pain in one instance, but another course of action in an identical instance.

Generally speaking, most LLMs default to non-determinism. Outputs with a random component are generally better for the generative applications most users want. This randomness is largely encapsulated in the sampling technique of the model: instead of giving a single token (roughly a part of a word), it gives several, from which a single word is selected. Techniques such as nucleus sampling and top-K sampling determine a list of potential words each with a probability of being the next word. The ‘temperature’ then controls how likely the top words will be sampled: 0 temperature and only the most likely word is taken and the higher the temperature the more random it gets.

However, it seems that even fixing these sampling techniques with a random seed and setting the temperature to 0 doesn’t guarantee determinism. I’ve been trying to find where the residual non-determinism slips in, but could only find this buried in openai’s documentation:

seed integer or null Optional

This feature is in Beta. If specified, our system will make a best effort to sample deterministically, such that repeated requests with the same

seedand parameters should return the same result. Determinism is not guaranteed, and you should refer to thesystem_fingerprintresponse parameter to monitor changes in the backend.

https://platform.openai.com/docs/api-reference/chat/create

Maybe this will be perfected during beta development, but I’d still love to know the source of the existing randomness (comment if you know).

It is for this reason that I believe that any medical study involving LLMs must replicate their findings at least several times. That way we at least get a sense of how likely any given LLM varies in its answers. How many times? That sounds like a research question, related to the more general problem of sample size determination for deep learning applications (more fraught than traditional power calculations in hypothesis testing).

But is a spread of answers necessarily bad? Ask any two healthcare professional to triage a patient and they may well give different answers if analysed at the syntactic level, but perfectly accord at the semantic level. One may say the that the ‘patient is possibly having a heart attack and needs to go to resus’, while the other says the ‘patient is having an MI and needs immediate attention’. Syntactically very different, but with very similar meanings. In computational lingo we might say that they are syntactically very distant but semantically close. The latter space of meaning is the one humans care

This has been referred to as the semantics problem in medicine, where medical ontologies exist in a morass of data embedded in a high dimensional space. This is related to a well known problem in LLMs: hallucinations.

Hallucinations

That LLMs hallucinate is well known. However, the term itself is vague and naturally lends itself to anthropomorphisation. The simplest definition I have come across is that they are seemingly credible but incorrect responses.

The implications for this in medical practice are obvious. The worst hallucinations are those which are plausible: a lie shrouded in a veil of truth. They remind me of those worst of coding errors – where everything seemingly works as expected, but some little bug is waiting for the moment to bite.

One attempt is simply to prompt an LLM multiple times and in some way take the consensus output. However, if the majority are hallucinating then the answer will be wrong: science is not democratic, in the sense that nature, not opinion (human or otherwise), is the arbiter of correctness.

A recent attempt to detect a type of hallucination (confabulations – just factually incorrect as opposed to intentionally lying) uses a concept called semantic entropy to detect hallucinations- they try to assess how likely it is a given output belongs to a given meaning ‘group’. The hope is that by comparing a number of outputs given the same prompt they can measure the ‘uncertainty’ in the LLM and so steer it to saying ‘I don’t know’ where appropriate, which would be significant improvement.

Popular at the moment is retrieval augmented generation (RAG). This prefaces the LLM prompt with relevant information, perhaps in the medical case such as presenting complaint, relevant medical literature, or a pertinent entry from the BNF. Such context has been consistently shown to improve the accuracy of reports. In a medical context these have been proposed to be used with knowledge graphs, which relate medical information as nodes in a network, connected via edags to the degree which they are related in the clinical world.

I have also heard of people using more LLMs to detect LLM hallucinations: I have yet to explore this branch, but immediately the question of who’s watching the watcher pops up.

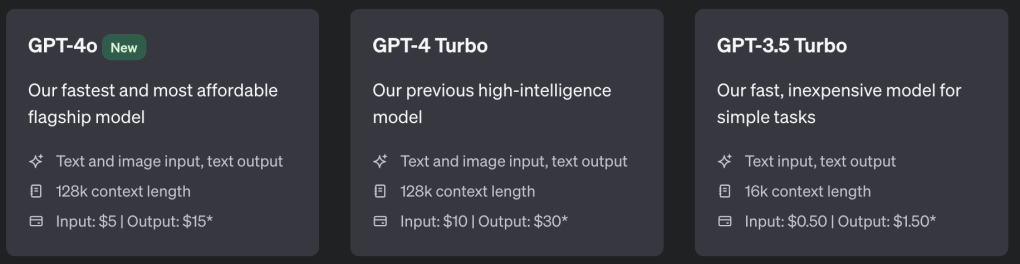

Cost and Computation

Another concern I would have for medical applications of LLMs are related to the models incentive structure. At the moment, for GPT, you pay for the number of input tokens and then pay three times that for output tokens. I personally find GPT to be particularly verbose, and this price structure might be at least part of the reason: it would make sense to incentivise the model to give more outputs and make more money. It’s annoying, but in a medical context is potentially dangerous. Usually when I read medical notes I was looking for a particular piece of information; the more words that is buried under then the longer it takes to find and the more likely to miss it.

But that’s nothing intrinsic to the LLM itself, but rather the financial viability, which I know nothing about. There are a number of open-source LLMs available, and while commercial LLMs typically out-perform open-source LLMs, the gap is narrowing.

In a society trying to decarbonise, LLMs seem like an extremely inefficient way completing tasks. This is especially the case in proposals when multiple LLMs are used for a single prompt: either to get a consensus output or to police other LLMs.

The cost in not only financial, but environmental. Despite a pledge to be carbon neutral by 2030, Microsoft’s carbon output has actually increased by 30%, fuelled in part by generative AI. These are extremely resource intensive methods, especially in training, but even in inference especially when applied at scale. If more efficient methods exist, they should be favoured.

Ethical Concerns

Speaking of training, LLMs require a vast corpus of data to learn the statistical patterns amongst tokens. Despite hopes that smaller, medically specialised LLMs, might be more efficient and better suited to clinical tasks, generally trained LLMs, such as GPT, still outperform specialist LLMs across most measures. As such it is likely people will continue to experiment with commercial LLMs. This involves submitting patient data to companies with servers that may be outisde of your country and legal jurisdiction. Though such inputs could be pseudo-anonymised, patient identifiable data may remain. This is not just a theoretical concern, with leading neuro-radiologists calling into question the waiving of ethical approval for a LLM in the radiology domain.

These concerns could be easily circumvented by using locally deployed open-source LLMs, although whether they are sufficiently trained to be clinically useful is another question.

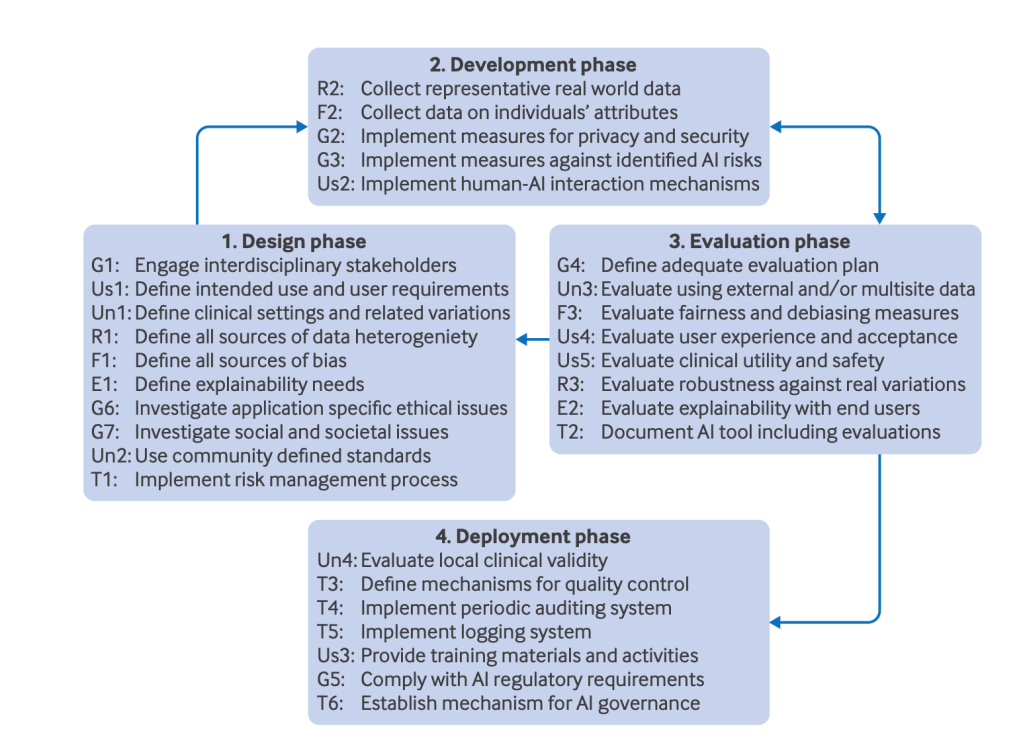

I must admit that the regulatory landscape is not one in which I enjoy a stroll, but LLMs deployed in many clinical settings would require approval as medical devices. This sets a high bar for commercial deployment of such tools: the research community should be similarly beholden to such standards.

The Future is Multimodal

LLMs are already being combined with vision encoders for vision-language generalist AIs. PathChat allows users to input histopathology images and ask questions about the image. It’s a great demonstration of what generative AI could offer medicine in the future. For now, it needs to be thoroughly validated, as with any healthcare technology,

PathChat achieved a diagnostic accuracy of 87% on multiple-choice questions. While this was better than it’s AI competitors, is this good enough for clinical deployment? This is like taking four new medications and assessing how they compare against each other. It tells you something, but does it tell you want you really want to know – whether the system is good enough and safe enough to be used in clinical practice. Assessing the relative strengths of systems does not tell us that: This is like taking four new medications and assessing how they compare against each other, but not assessing their absolute performance against some clinically relevant biomarker.

Final Thoughts

We don’t expect humans, even clinical experts, to be perfect. Current healthcare systems are generally robust enough so that single point of failure should not have overly deleterious effects for a patient: if there is a surprising result, then that result isn’t taken in isolation, but sits within a complete clinical picture – which includes occasional technical failures. The simplest anecdote from my practice was an otherwise well patient ready for discharge but with an inexplicably high blood sugar level. Rather than treating the patient based on this single result which just didn’t fit the clinical picture we recalibrated the glucometer to find the fault was with the machine. As AI in general becomes increasingly embedded into clinical practice, we should bare this in mind. LLMs are a tool, and like any tool it will have its strength and weaknesses, and it is up to the person wielding the tool to understand them. The more powerful the tool, the more important is this understanding. LLMs, with current model architectures, hallucinate. While technical efforts to reduce this should continue, it is an intrinsic feature of how such models are trained.

AI, including LLMs, will fail in ways surprising to us. Humans also fail in all manner of ways. We should construct systems that leverage the strengths of each, while catching each others failures.

I use LLMs a lot (though never for writing, not even emails which apparently is becoming common). They are great for many tasks, especially creative ones where I want the model to make stuff up, but even as a study guide when paired up the Wolfram (which essentially makes it RAG), as long as I know enough about the subject to tell when it’s gone off the rails. However, they always feel like one of those shopping trolleys with a wayward wheel that always wants to veer off to the left, then when you try to correct it lurches over to the right. It’s a tool looking for an application. I have no doubt it will find many, but the and risks (that clinicians become so used to it that they stop engaging their own brains)

LLMs are a solution looking for a problem. The current hype of LLMs is at least doing one useful thing: making healthcare practitioners think about what they want from such technology. Existing LLM architectures are fundamentally flawed if veracity is desired: they fundamentally aren’t trained for it. It may be that some addition to LLMs, like RAG, might be able to steer it to be good enough for clinical use: I personally doubt it. By stating our desiderata, healthcare professionals can signal to computer scientists what the next LLM architectures should be at their core: not generative AI but curative AI.

Leave a comment